The short answer is, no. The Singer decision is narrow, non-binding, leaves other parts of the ordinance in place, and expressly leaves the door open for Newton (and other state and local governments) to enact more narrowly-tailored regulations on drones.

In a way, the four challenged provisions of the Newton ordinance were an easy call, because each conflicted with or effectively usurped existing FAA regulations. This allowed the court to invoke the doctrine of “conflict preemption,” as opposed to what is called “field preemption.”

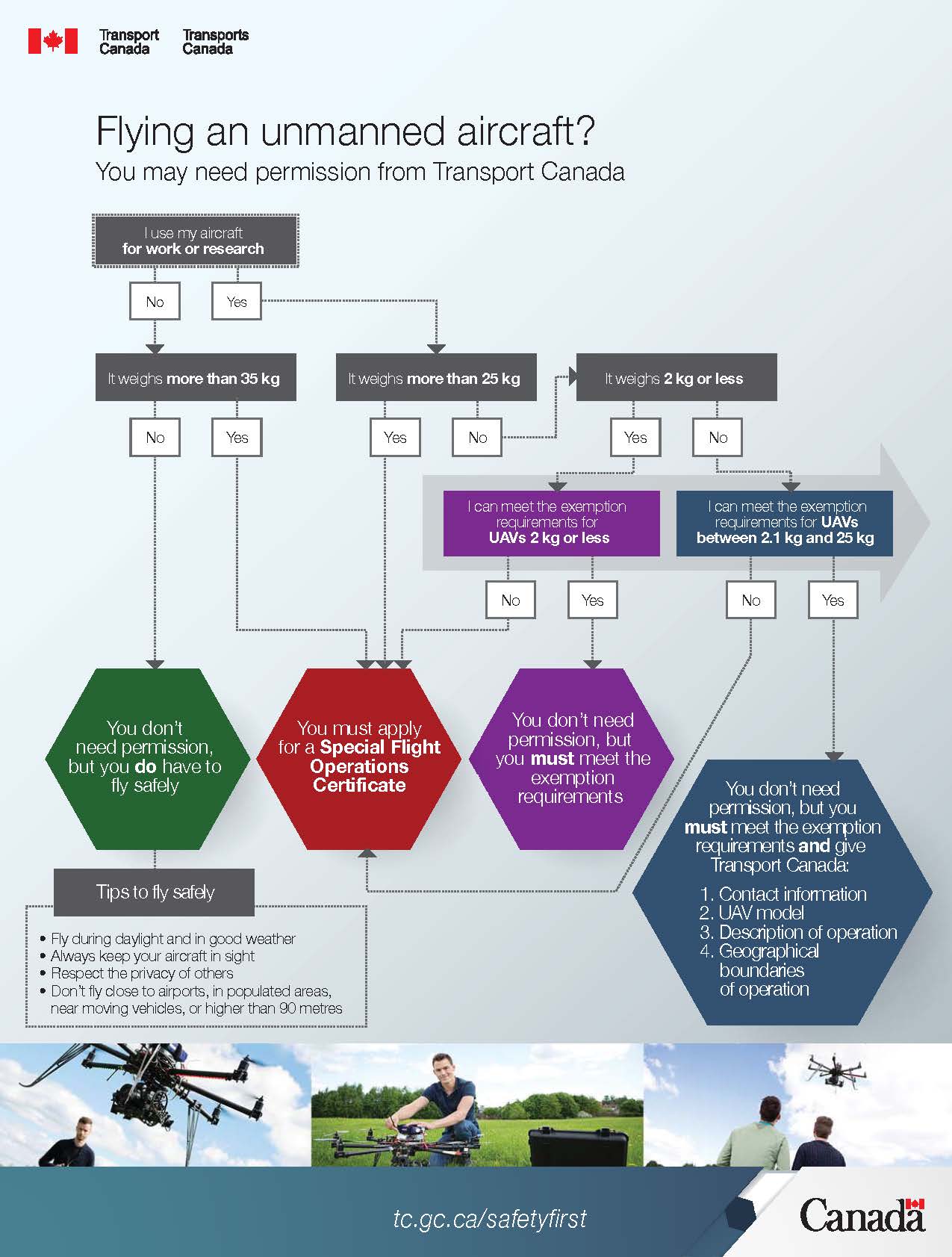

“Field preemption” is invoked when the federal government occupies the entire field of an area of regulation that is within its Constitutional authority, even though it might not have enacted a specific regulation pertaining to the challenged state or local law. Significantly, the court rejected field preemption because the FAA has expressly left the door open to some state regulation of drone use (such as the privacy protections of Florida’s FUSA statute, which I discussed, here).

“Conflict preemption” means exactly what it implies: That when the federal government regulates an area within its Constitutional authority, those regulations are the supreme law of the land and the states may not enact laws that would contradict or undermine the federal regulation.

Briefly:

Section (b) of the Newton ordinance provided that “[o]wners of all pilotless aircraft shall register their pilotless aircraft with the City Clerk’s Office, either individually or as a member of a club . . . .” Because the FAA has held itself out as the exclusive authority for registration of aircraft, striking down this provision of the ordinance was that rare bird in litigation: a no-brainer. This is probably the broadest part of the decision, in that the court made it clear that the city may not require any kind of drone registration, period.

The ordinance at subsection (c)(1)(a) prohibited drone flights below an altitude of 400 feet over any private property without the express permission of the property owner. Also, subsection (c)(1)(e) prohibited flying drones over public property, at any altitude, without prior permission from the city. The court found that these provisions had the effect of banning all drone flights in the city, because FAA regulations restrict sUAS flights to below 400 feet AGL. While the FAA left the door open to some local regulation of drones, that should not be interpreted as license to effectively ban drone operations. This leaves the door open to the possibility of a more narrowly-drawn ordinance.

Finally, subsection (c)(1)(b) of the ordinance prohibited drones from being operated “at a distance beyond the visual line of sight of the Operator.” This was plainly duplicative of Part 107 and, as such, tended to usurp an express regulation of the FAA (which could, at some time in the future, change its mind about BVLoS operation).

The decision ends with a note that Newton is welcome to craft narrower regulations. Precisely what those regulations will look like is hard to say.

Whatever the case may be, one should not take this as an invalidation of drone regulations in one’s particular state or city. The court only addressed these specific provisions of the Newton ordinance, and the decision has no binding effect on other courts, let alone other states and municipalities.

But let us not detract from the significance of this win, either. Major kudos are in order for the petitioner, Dr. Michael Singer, and his attorneys.