As our readers know, the NTSB has confirmed the FAA’s assertion of jurisdiction in the Pirker case to cite hobbyists for the reckless operation of model aircraft. Last week, we pondered how to define the boundaries of that jurisdiction, using the Commerce Clause as a point of reference.

Regardless of what one may think of the NTSB’s logic, based on the broad, post-New Deal interpretation of the Commerce Clause it is at least conceivable that the FAA’s jurisdiction extends that far. But we think that Congress has already signaled a different approach.

FMRA section 336 specifically excludes model aircraft from regulatory oversight, except as to those operators “who endanger the safety of the national airspace system.” This seems like a clear statement that the FAA’s authority to regulate model aircraft is risk-based. In other words, the FAA should look not at whether a particular device is capable of flight, but at the nature of the activity in question, and the risk that a particular device is likely to pose to the national airspace.

This of course requires a fact-based analysis, which will vary, case by case. But it doesn’t mean that the FAA can’t draw reasonable, bright lines on what it should regulate, and what it should leave alone. In fact, it’s already been done, quite close to home.

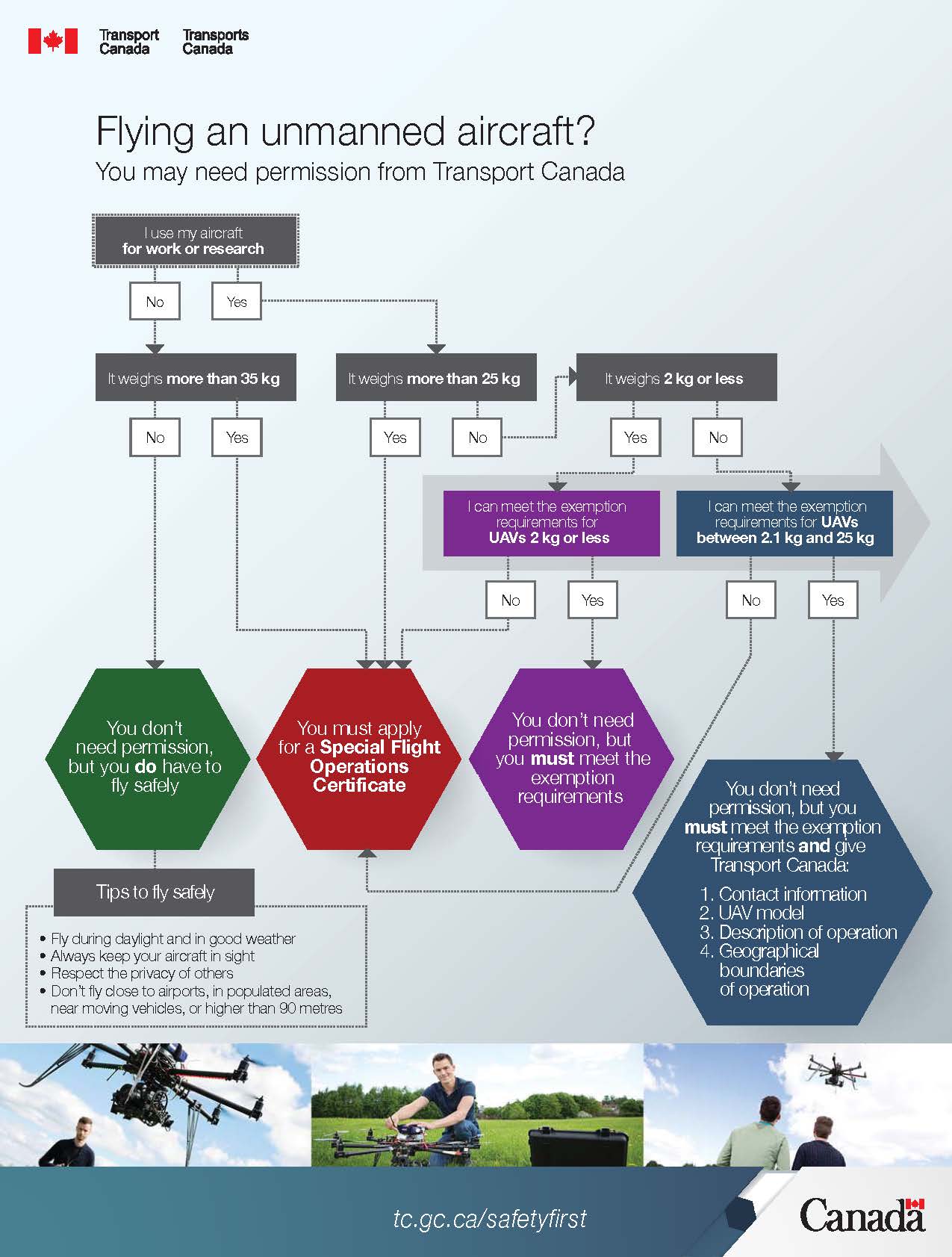

Transports Canada has recently published a very simple explanation of its own, risk-based jurisdictional approach for sUAS. This graphic lays it out in a single page:

This is remarkably sensible. If you’re a hobbyist, and your drone weighs 35 kg or less, then use common sense and happy flying. The rules for exempt professionals are also clear.

We would urge the FAA to take a close look at it.